In the sweep of history, four years isn't even the blink of an eye. But, even at my age--when you start to think of people within fifteen years or so of your own age as your peers--four years, especially if they're anything like the ones that have just passed, can seem like a geological age.

I'll spare you the cliche that "we are living in a different world" from that of 2019. (OK, since I've mentioned it, I didn't spare you from it, did I?) I have seen changes in my Astoria, New York neighborhood and in the city as a whole. The passage of time, however, seems all the more sweeping when you return to a place you haven't seen in a while, especially if that place doesn't change as much or as quickly as your own environs.

While Paris is a modern city in terms of technology and infrastructure, its overall appearance doesn't change nearly as dramatically as that of New York in any given period of time. You can count on returning to a building you saw in the City of Light four, fourteen or forty years ago. Even some of the stores, restaurants and cafes you remember will be there if you return. So, perhaps, that quality makes any change all the more striking.

In my case, I couldn't help but to notice how many more people were on bikes than I saw during previous visits. I'd heard and read that many people took to riding--for transportation, recreation and fitness--during the pandemic. Apparently, they stayed in the saddle. Of course that makes me happy. I also noticed, on the other hand, e-bikes and scooters, which were nowhere to be seen the year before the pandemic. I saw the proliferation of those vehicles in New York as the first weeks and months of the pandemic turned into years, but in Paris, it seemed as if they were all superimposed on the image I had of the city from the last time I saw it.

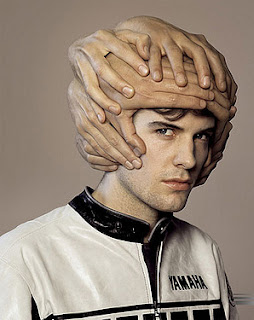

One thing hasn't changed, though: Almost no scooter-rider or cyclist, whether of the completely human-powered or electric variety, was wearing a helmet. I admit that I didn't wear one, either: It's not the easiest thing to pack, especially if you're traveling only with a carry-on bag. But somehow I didn't feel as vulnerable or exposed as I do when I leave my apartment avec velo, sans casque.

I got to thinking about that when I came across this article. It points out, correctly, that the obsession with helmet-wearing is mainly an American one. As the article's author, Marion Renault, points out, few cyclists in the Netherlands don the plastic and foam shells. One reason, according to Renault, is that the Dutch feel safer while riding: Their infrastructure lends itself to safe cycling to a much greater degree than what we have in the 'States. Also, Dutch drivers' awareness and attitudes towards cyclists are very different from those of their American counterparts.

Something similar could be said, I think, for Paris and France, if to a lesser degree. Certainly, I felt safer, whether I was riding on a protected lane or in traffic. About the latter: Even though Paris streets are narrower than those in New York, I felt as if I had more room to maneuver. Most likely, that had something to do with the fact that vehicles are smaller and lower to the street: You don't often see anything like America's best-selling vehicle class: the Ford F-Series, which weighs 7500 pounds and has a hood that stands four and a half feet tall--about the height of an adult's chin.

That brings me to another point Renault makes: most helmet testing does not, and cannot, measure the impact of a collision between such a vehicle and a cyclist. For one thing, it's all but impossible to replicate such conditions in a laboratory. There are more variables in such collisions than there are in, say, a clash between (American) football players.

One of those variables, as I implied earlier, is the driver him or her self. When I was doored two years ago, a nurse in the emergency room declared, "Good thing you were wearing your helmet." While that was probably true, I would have been safer had the driver glanced out her window and seen me on the other side before she opened her door. I think a lot of French and Dutch riders would agree. They also know that having good bike lanes, room to maneuver and traffic regulations that makes sense do at least as much as any piece of protective gear to promote their safety: Their cyclists' rates of injury and death are much lower than those of their American counterparts.

So, if and when I return to Paris or Amsterdam, or anyplace else in France or the Netherlands, will I see as few cyclists wearing helmets as I saw during the trip I just took?