Today I will, once again, invoke the “Howard Cosell rule.” Thus, today’s post will only tangentially, if at all, relate to cycling or bicycles.

In previous posts, I have mentioned athletes whom I respect as much as human beings as I admire them for their athletic talents and performance. That list is, and can never be, complete because of people like Willie Mays.

While I have wonderful memories of his hits and plays, I really didn’t know much about his life or career before playing for the New York and San Francisco Giants and New York Mets. I knew he had played briefly in the Negro Leagues, as Jackie Robinson—one of my heroes—did. But I am ashamed to admit that he endured much of the same bigotry and threats of violence as Robinson did. That isn’t surprising when you consider that Willie made his major league debut only four years after Jackie—and that both played their Negro League games in a city where Black and White players weren’t allowed on the same field. That city later became synonymous with some of the worst violence that was part of the resistance to the Civil Rights movement.

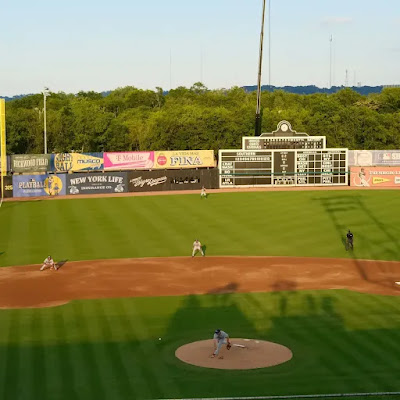

I am talking about Birmingham, Alabama. Willie Mays began his career there—and his life just outside the city. Last night, one of his former clubs—the Giants—faced the St. Louis Cardinals at Rickwood Field, where Mays played his first professional game.

That game was supposed to be a tribute to Mays, the Negro League team—the Birmingham Black Barons—for which he played and to the many Negro League players—like Henry Aaron—who became stars in the Major Leagues after they integrated.

Sadly, however, Willie Mays passed away two nights earlier, at 93 years old. Still, the game was all about him. And the twenty-four former players in attendance—most of them enshrined in the Hall of Fame, wouldn’t have had it any other way.

They included Reggie Jackson, whom many regard as the greatest baseball player to follow Mays. While he never put on the Black Barons’, or any other Negro League team’s, uniform, he faced many of the same taunts and threats Mays, Robinson and Aaron endured a decade earlier. Jackson began his professional career with the Kansas City (later Oakland) Athletics’ minor-league team in Birmingham not long after police chief “Bull” Connor dispersed Civil Rights protesters with a water cannon. Even after Federal civil rights laws passed, Birmingham—and to be fair, many other places in the South, North, East and West—operated under various forms of de facto if not de jure segregation. So, Reggie was refused service in restaurants and wasn’t allowed to stay in hotels with the rest of his team: the same sorts of abuse Jackie, Willie and Henry endured a generation earlier.

But zfor all the history I have just given you, dear reader, I am sad about Willie Mays’ passing because he was one of the first true superstar athletes I saw live. Although it was late in his career—during his last few years with the Giants—I could see that he was special, as a baseball player and a person. Watching him, even when he stood still, you could feel the joy he felt. And he could say, matter-of-factly, he was the best player and nobody, not even the other players I’ve mentioned or Mickey Mantle or Joe DiMaggio—whom Mays idolized while growing up—would challenge him. Now that I think of him, I see a combination of the best qualities of Muhammad Ali, Magic Johnson and perhaps “Major Taylor.”

Perhaps the greatest accolades came from two performers of a different kind. Frank Sinatra once him, “If I could play baseball like you, I would be the happiest man in the world.” And Tallulah Bankhead declared, “There have been only two geniuses in this world: Willie Mays and Willie Shakespeare.”

As Reggie Jackson and others pointed out, he may not have made it to last night’s game. But he was there. And he will be here for many of us.