Yesterday, I wrote about something that might encourage more people to cycle: more safe and convenient bicycle parking.

Ironically, some planners and entrepreneurs thought that eliminating bicycle parking--or, more precisely, the need for it-- would make bicycle-share programs more convenient and popular. Too often, though, dockless share systems resulted in bikes abandoned on sidewalks, in stairwells or wherever else the rider stopped riding it. That was not only an inconvenience; for people with limited mobility, a bike lying on its side in the middle of a sidewalk or path can be an obstacle or even a hazard.

In some Chinese cities, the bikes filled not only sidewalks and other public spaces, but also parking pens, fields and landfills. One reason is that in those cities, where some of the first dockless share systems were launched, they were run by private companies like Ofo (which also ran some programs in the US and other countries) with little or no communication with, let alone oversight from, local or regional government agencies.

According to a "Future Planet" article on the BBC website, the Chinese bike share saga can serve as a lesson on what makes for at least one part of a successful bike share program. Once, when I was very young (which, believe it or not, I once was), I believed that simply allowing innovators and entrepreneurs to "slug it out" would result in the best possible goods and services at the lowest possible prices. Perhaps it wouldn't surprise you to know that at that point of my life, I had immersed myself in Atlas Shrugged and other Ayn Rand works, in addition to other fantasies.

One problem with allowing what is, essentially, anarcho-capitalism, is that the businesses in question have no incentive to deal with the consequences of their work. Think of the pollution and other environmental consequences of unchecked industrial development.

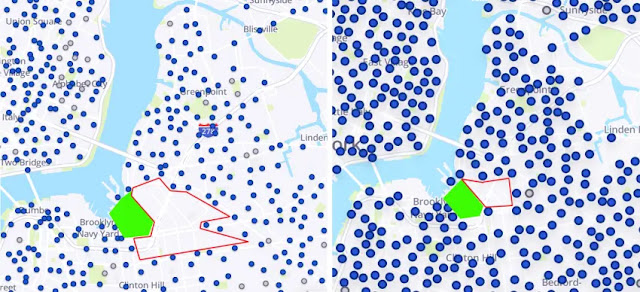

Another problem is one that I see in, interestingly, the subway (metro) system of New York, my hometown. Different parts of the city's rapid transit system were developed by individual companies. As a result, stations are clustered in relatively few areas while other parts of the city are transportation "deserts." For instance, on the "Q" line in Brooklyn, the distance between the Beverly Road and Cortelyou Road stations is so short that when the front of a train enters one station, the rear is still in the other! The distance between the 14th and 18th Street stations on the #1 line in Manhattan isn't much greater. But Floyd Bennett Field, where I sometimes ride (and a very interesting place), is about seven kilometers from the nearest subway station. Compare that to, say, Paris, where no point in the city is more than 500 meters from a Metro station and where correspondance (transfer points) are convenient.

|

| From the BBC site, credit to Getty Images |

How does that relate to bike share programs? Well, according to the article, another problem with allowing unregulated companies to run bike share programs is that they generally do little or nothing to integrate their systems with bike lanes or other bicycle infrastructure--or with existing transit systems. Most people won't ride to school or work if it's more than half an hour's ride from their homes, but they might ride to a train, bus, ferry or other mode of transportation if they can park their bikes--or if bikes were allowed on mass transit.

(Cities in Africa and Asia that are densely populated but where few own cars could be developed to accommodate cyclists and would be good opportunities for bike share programs. They could avoid the problems experienced by, say, Chinese cities that rapidly switched from bikes to cars.)

The BBC article points to some other factors that make for successful bike share programs. One is topography: Most popular bike shares are in relatively flat cities. (That is a reason why Citibike has been so widely used in New York, a city with relatively little bike infrastructure or integration with other forms of transportation.) One way to make bike shares work in less horizontal locales is to offer incentives for leaving bikes on tops of hills.

Also, bike shares have been most successful in cities that are compact: Again, Paris comes to mind, along with places like Amsterdam and Copenhagen. This fact could also

In brief, bike share programs are not "one size fits all" propositions: They have to be integrated with other forms of bicycle infrastructure as well as other transportation systems, and have to be tailored to their locales in various other ways. And share operators need support and oversight from local officials. But, as the experience of successful programs has shown, bike shares can be an integral part of a city's transportation structure, and can enhance its quality of life.

.jfif)