In the military, and in other large, bureaucratic organizations, it's often said that it's "easier to get forgiveness than permission."

What that means is that if you know something is useful, constructive or just good, it's best just to go ahead and do it rather than to wait for approval, which might be denied because of some technicality or mere whim.

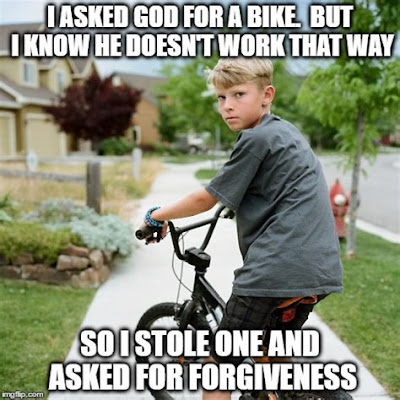

One thing is for certain: Whatever you want to do, or get, won't come as a result of prayer. Such great minds as Huckleberry Finn have reminded us of that:

What that means is that if you know something is useful, constructive or just good, it's best just to go ahead and do it rather than to wait for approval, which might be denied because of some technicality or mere whim.

One thing is for certain: Whatever you want to do, or get, won't come as a result of prayer. Such great minds as Huckleberry Finn have reminded us of that:

Miss Watson

she took me in the closet and prayed, but nothing come of it. She told me to

pray every day, and whatever I asked for I would get it. But it warn't so. I

tried it. Once I got a fish-line, but no hooks. It warn't any good to me

without hooks. I tried for the hooks three or four times, but somehow I

couldn't make it work. By and by, one day, I asked Miss Watson to try for me,

but she said I was a fool. She never told me why, and I couldn't make it out no

way.

Well, it seems that someone has, at a very young age, internalized the lessons of Huck and the Army:

Let's hope that he retains his healthy cynicism about prayer and forgiveness--but learns that stealing is, well, not good for one's karma.