In October 1964, Tetsuo Maeda filed a patent application in Japan for what would become, in my opinion, one of the two or three most important derailleur innovations in history.

It was the brainchild of his chief designer, Nobui Ozaki. He was no doubt trying to make a derailleur that was easier to shift and shifted more accurately than the ones available at that time. Did he realize that it would influence derailleur design for the next half-century? Did Maeda, the owner of the company that employed Ozaki, know that for two decades, other derailleur manufacturers would wait, with bated breath, for his patent to run out?

Well, both of those scenarios came true. You see, the patent Maeda filed in his home country--and a month later in the US--would cover a design still used today, in one form or another, on any rear derailleur that has even a pretense of quality.

I am talking about the SunTour Gran-Prix. Over the next few years, SunTour would refine its design. For one thing, it would replace its original single-spring design (The same spring that operates the parallelogram also tensions the chain cage.) with separate springs for each function. And steel parts would be replaced by alloy ones, which in turn would become more sculpted and rounded.

The result was that the 1964 Gran Prix

would evolve into the first "V" derailleur in 1968.

I would put one of those on one of my bikes. I mean, how can you not love a derailleur with those pivot bolts?

Of course, the V was further refined and became the V Luxe. One thing I find interesting about the V and V Luxe is that they were lighter than most derailleurs made at the time--or even today.

The V, according to Michael Sweatman of Disrealigears, weighed 218 grams. That is only 13 grams (less than half an ounce) more than another influential derailleur that came out exactly 50 years ago

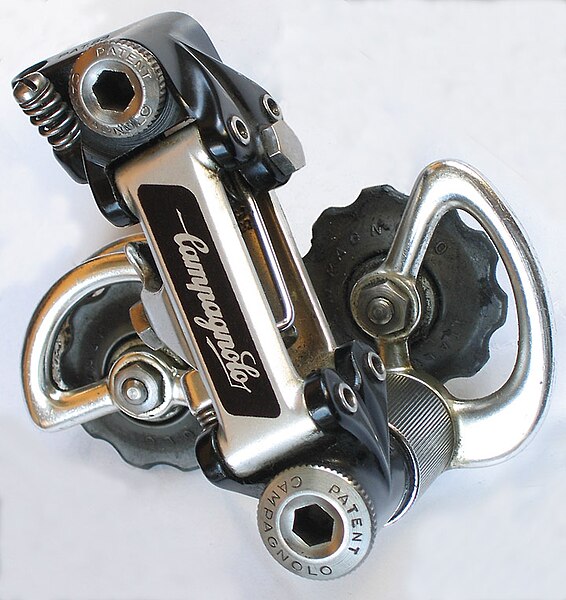

yes, the Campagnolo Nuovo Record--which, of course,was a refinement of the earlier Record and its progenitor, the first Gran Sport parallelogram rear derailleur.

For comparison's sake, the 1968 SunTour V weighs almost exactly the same as a Shimano Ultegra 6400 (introduced in 1988), 6401 (1992) or 6500 (1998)--or the Dura Ace 7402 (made from 1989 to 1996), all of which are in the 210 to 220 gram range. Later DA rear derailleurs (the 7700 series onward) shed 10 to 15 grams--and that with the use of a titanium upper pivot bolts!

The funny thing is that no matter how light a component is, someone wants it even lighter. So I guess I shouldn't have been surprised to find this

I mean, how much weight did those holes take out of that "V" derailleur?

I guess I shouldn't be too critical, though. After all, not only was the Campy NR drilled out--or, sometimes, slotted in its parallelogram--so was the lightest rear derailleur of them all:

In case you were wondering: The Huret Jubilee weighed 145 grams--before anyone touched it with a drill, mill or lathe!

It was the brainchild of his chief designer, Nobui Ozaki. He was no doubt trying to make a derailleur that was easier to shift and shifted more accurately than the ones available at that time. Did he realize that it would influence derailleur design for the next half-century? Did Maeda, the owner of the company that employed Ozaki, know that for two decades, other derailleur manufacturers would wait, with bated breath, for his patent to run out?

Well, both of those scenarios came true. You see, the patent Maeda filed in his home country--and a month later in the US--would cover a design still used today, in one form or another, on any rear derailleur that has even a pretense of quality.

I am talking about the SunTour Gran-Prix. Over the next few years, SunTour would refine its design. For one thing, it would replace its original single-spring design (The same spring that operates the parallelogram also tensions the chain cage.) with separate springs for each function. And steel parts would be replaced by alloy ones, which in turn would become more sculpted and rounded.

The result was that the 1964 Gran Prix

would evolve into the first "V" derailleur in 1968.

I would put one of those on one of my bikes. I mean, how can you not love a derailleur with those pivot bolts?

Of course, the V was further refined and became the V Luxe. One thing I find interesting about the V and V Luxe is that they were lighter than most derailleurs made at the time--or even today.

The V, according to Michael Sweatman of Disrealigears, weighed 218 grams. That is only 13 grams (less than half an ounce) more than another influential derailleur that came out exactly 50 years ago

yes, the Campagnolo Nuovo Record--which, of course,was a refinement of the earlier Record and its progenitor, the first Gran Sport parallelogram rear derailleur.

For comparison's sake, the 1968 SunTour V weighs almost exactly the same as a Shimano Ultegra 6400 (introduced in 1988), 6401 (1992) or 6500 (1998)--or the Dura Ace 7402 (made from 1989 to 1996), all of which are in the 210 to 220 gram range. Later DA rear derailleurs (the 7700 series onward) shed 10 to 15 grams--and that with the use of a titanium upper pivot bolts!

The funny thing is that no matter how light a component is, someone wants it even lighter. So I guess I shouldn't have been surprised to find this

I mean, how much weight did those holes take out of that "V" derailleur?

I guess I shouldn't be too critical, though. After all, not only was the Campy NR drilled out--or, sometimes, slotted in its parallelogram--so was the lightest rear derailleur of them all:

In case you were wondering: The Huret Jubilee weighed 145 grams--before anyone touched it with a drill, mill or lathe!