I remember getting my first Campagnolo

component: a pair of Nuovo Tipo

hubs. My first nice pair of clincher wheels—Super

Champion 58 rims laced to those hubs with Robergel Sport spokes—cost the

princely (for a poor college student like me) sum of $100. The man who built them seemed like a magician

to me at the time: I simply could not

fathom what sorcery or alchemy turned all of those parts into a pair of wheels

that would take the length and breadth of state of New Jersey, on two of the

early Five Boro Bike Tours and on my first European bike tour.

It wasn’t just the parts and the build that

made them seem almost otherworldly at that time. Most clincher tires and wheels in the US at

the time were 27” and the tubes had Schraeder (the kind found on car tires)

valves. Mine were 700C and drilled for

Presta valves. That was

intentional: I used the wheels on my

Peugeot PX-10, which came with 700C tubular wheels and tires—and, of course

Presta valves. I’ve never seen a tubular

tire with Schrader valves and the only non-700C tubulars I’ve come across were

the ones made for junior racers.

Those new wheels meant that I could switch back

and forth between tubulars and clinchers without having to re-adjust the brake

blocks. (I used to tighten the cable

adjuster a bit for the tubular rims, which were narrower and loosen them for

the clinchers.) They also would fit on

other good bikes, including a couple I would acquire later—and which would, at

one time or another, be equipped with those wheels. Also, I could use the same pump on all of my tires without having to use an adapter.

Today, those wheels would seem dated to anyone not

riding a “classic” bike. The parts were

all of fine quality and lasted many rides for me. But using those Tipo hubs would limit gear

selection to whatever five- and six-speed freewheels could be found in swap

meets, on eBay or in some “accidentally” discovered stash. And, as good as

those rims were, the Mavic MA series rims, with their double-wall construction

and hooked tire beads, introduced in the early 1980s, were lighter and allowed

cyclists to use a wider variety of tires.

But even after the MA rims—and newer hub offerings from Campagnolo, Shimano,

Mavic and other companies—were introduced, there were places where cyclists

would have done almost anything to have wheels like my first good clinchers. One of those places was the German Democratic

Republic, a.k.a. East Germany. In fact,

they probably would have done illegal or simply un-approved-of things to get a

bike like mine—especially its Stronglight crank. Only Campagnolo’s Record crankset was more

prized.

That is the situation Gerolf Meyer describes in

the latest edition of BicycleQuarterly.

Like other athletes from his country, cyclists

wanted to prove themselves against the best from the West. As talented as some East German riders were,

their equipment was stuck in the 1950’s.

There were shops that took “room dividers”—Diamant “sport” bicycles with

impossibly long wheelbases—and shortened chain stays and top tubes, lowered

brake bridges and did other things to make those machines ride something like

racing bikes. Engineers and technicians

in factories and medical supply cooperatives made cable tunnel guides and other

frame fittings and bike parts on the side.

There were even mechanics and builders who could

take the crudely-machined and –finished East German components and make them

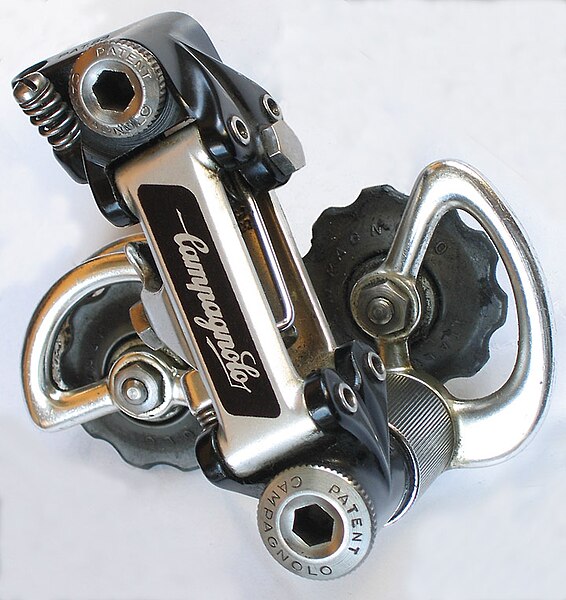

look—and even, to a degree, function—like “Campag”. In one of the most extreme examples,

Hans-Christian Smolik took a Tectoron rear derailleur—which borrowed its shape

and basic function from the Campagnolo Record but and had lettering that faced

upside down—and made it all but indistinguishable from the Real McCoy.

In the 1980s, the East German sanctioned the

development of the Tectoron derailleur and other parts in an attempt to catch

up with the technology of Western bikes and equipment. One of the ironies is that Campagnolo,

Shimano, Mavic and other Western manufacturers were innovating in ways that

would render obsolete (at least for those who simply had to have the newest and latest)

the stuff the East Germans were imitiating.

A fortunate few were able to obtain Western

components through connections—a relative who’d retired to the West (Apparently,the East

German government didn’t mind letting retirees leave, probably figuring that it

would save the state on pension costs.), a partially-subterranean “supply chain”

or Western racers the East Germans met at events like the Peace Race.

About the latter: There developed a

barter system not unlike the ones soldiers develop with those fighting

alongside, as well as on the other side, of them, complete with its own "exchange rates". (During the first Gulf War, one

French K-ration was worth five of its American counterparts.) Sometimes

the East Germans—as well as Soviet bloc riders—would trade jerseys, pins

or other souvenirs, or local delicacies. But the East Germans—and Czechs—actually

made one bicycle component that was superior to anything in the West: tubular

tires. Kowalit tubular were the stuff of

legend: a light, supple tire that wore

like iron. I never rode any myself, but

I did have a pair of Czech-made “Barum” tires that I rode, literally, to the tubes: Not even the best stuff from Clement,

Vittoria, Wolber, Michelin, Continental or Soyo (Yes, I rode tires from every one of those companies!) was anywhere near as good. Ten Kowalits --or, I presume, Barums-- could

fetch a good wheelset.

Of course, such deals had to be made “in the

shadows”, and certainly not after the race.

Can you imagine what some East German would have offered (if indeed he

or she had anything to offer) for my old Colnago?