Today is International Women’s Day.

Whatever your gender identity or your anatomical configuration, if you are a cyclist, you should recognize the importance of women in cycling and, well, the world. For one thing, we are the majority of humanity. For another, there have been many great female cyclists, most of whom have ridden without recognition and support. A few, including Beryl Burton, have even beaten men’s records.

But perhaps the most important reason of all is that anyone who cares about gender equality needs to recognize the role the bicycle has played in the long journey toward that goal. After all, Susan B. Anthony said that the bicycle did more to liberate women than anything else. (That is why oppressive regimes like the Taliban forbid or discourage women and girls from riding them.) Bikes provided, and continue to provide, independent mobility. They also released women from the constraints of corsets and hoop skirts which, I believe, helped to relax dress standards—and thus make cycling easier—for everyone.

Today also happens to be the anniversary of two events that occurred during my lifetime. One is one the greatest aviation mysteries of all time: the disappearance of Malaysia Flight 370 ten years ago. Such an incident would have caused consternation in any time, but have become much rarer over time.

While that tragedy may not seem to have much in common with bicycles or bicycling, the other event is somewhat more related. On this date in 1971,”the fight of the century” took place between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali. Joe won that bout, but Ali would win two rematches.

To this day, I can’t recall another sporting event-and very few events of any kind-that were preceded by as much anticipation and hype. I’m no boxing expert, but I doubt that there has ever been a title match between two opponents so equally matched in talent and skill but so different in style. Also, Ali had been stripped of his titles—and his boxing licenses—for three years because of his refusal to register for the military draft that could have forced him to serve in the Vietnam War.

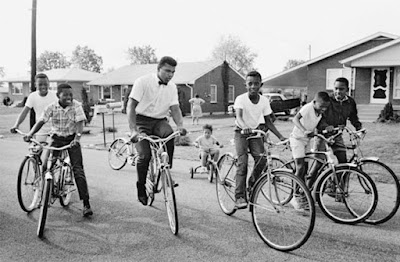

So why is “The Fight” worthy of mention on this blog? Well, as I mentioned in a previous post, a boy named Cassius Clay might never have grown up to become Muhammad Ali, “The Greatest,” had his bicycle not been stolen. In recounting his loss to á police sergeant, he vowed to “whup” the thief. The sergeant, who just happened to train boxers on the side, admonished young Clay that he should learn how to fight first.

So..did you ever expect to see Susan B. Anthony and Muhammad Ali mentioned in the same post—much less one that includes Malaysia Airlines Flight 370?