In less than a week, we've lost three people who, in different ways, helped to shape cycling culture in the US.

Perhaps the one closest to my, and many people's, hearts is Marty Epstein. If you are not from the New York-New Jersey area, or don't ride in randonees, brevets or gran fondos, you might not have heard of him. He did, however, start one of the first gran fondo rides here in the eastern US. It turned Morristown, New Jersey into a cycling mecca.

The town also just happens to be the locale for his shop, Marty's Reliable Cycle, where you could be just as comfortable buying a steel bike of any kind as you could if you were in the market for a Trek Madone or S-Works--or a basic commuter bike, or something for your kid. He once said his goal was to "change the world through bicycles." At least he understood that such change would involve all types of bicycles and riders, not just one subculture or market subset.

He went to the Gran Fondo in the sky last Thursday, at age 69, less than a year after being diagnosed with prostate cancer.

How many people who haven't won the Tour de France get a funeral procession like that?

On Sunday, someone who, perhaps, helped to plant the seeds of cycling culture in America passed at age 93. Unless you are a Schwinn historian or spend a lot of time looking at patent applications, you probably haven't heard of Frank Brilando. He raced in the 1948 and 1952 Olympics, but his long tenure as a Schwinn engineer earned him his place in cycling history. He, along with Al Fritz, created the Sting-Ray, Varsity and Continental bicycles during the 1960s.

You may think the Sting-Ray is an abomination only a 12-year-old boy could love, and you may turn up your nose at the Varsity and Continental. Before Brilando and Fritz developed them, however, few Americans had ridden a bicycle with a derailleur. Those Schwinns helped to popularize the multi-gear mechanisms and, arguably, paved the way for the Bike Boom of the '70s. If nothing else, the Varsity and Continental probably got American adults to ride bikes for the first time in decades.

Brilando and Fritz also worked on the Airdyne full-body fan-resistance exercise bike. Once, in a conference room in Taiwan, Schwinn's brain trust were trying to figure out the proper crossover pattern (the relationship between the rider's arm position on the handles and foot position on the pedals) when Brilando realized the best pattern would be reflected in the arm and leg coordination of a baby crawling on the floor. "So Frank gets down on the floor and starts crawling like a baby," Fritz, who died in 2013, recalled.

Over the same weekend, Roland Della Santa, died at his Reno home, aged 72. He began building bicycle frames in 1970. One of his creations won the "best road frame" award at the 2009 North American Handbuilt Bicycle Show. Like Brilando, Della Santa also raced, and sometimes the frames people ordered were delayed because he was training so much.

But a few frames of his in particular changed the course (pun intended) of American cycling. He took a certain 16-year-old into his home and admonished the young man for wearing a yellow jersey to his first race. "I didn't know you're only supposed to do that if you win the Tour de France," that rider recalls. Della Santa taught the young man about racing, and the European scene in particular. In fact, he inspired the youthful rider to plan a career in Europe.

Della Santa, of course, built frames for that young rider and became his first sponsor. When that rider achieved fame and fortune, Della Santa built the first stock steel frames sold under that cyclist's name.

Here's a hint to that rider's identity: He is the only rider from his country whose Tour de France victories haven't been vacated due to doping.

Yes, I am talking about Greg LeMond. You might say that Della Santa helped him to become what he became.

Perhaps the one closest to my, and many people's, hearts is Marty Epstein. If you are not from the New York-New Jersey area, or don't ride in randonees, brevets or gran fondos, you might not have heard of him. He did, however, start one of the first gran fondo rides here in the eastern US. It turned Morristown, New Jersey into a cycling mecca.

The town also just happens to be the locale for his shop, Marty's Reliable Cycle, where you could be just as comfortable buying a steel bike of any kind as you could if you were in the market for a Trek Madone or S-Works--or a basic commuter bike, or something for your kid. He once said his goal was to "change the world through bicycles." At least he understood that such change would involve all types of bicycles and riders, not just one subculture or market subset.

He went to the Gran Fondo in the sky last Thursday, at age 69, less than a year after being diagnosed with prostate cancer.

How many people who haven't won the Tour de France get a funeral procession like that?

On Sunday, someone who, perhaps, helped to plant the seeds of cycling culture in America passed at age 93. Unless you are a Schwinn historian or spend a lot of time looking at patent applications, you probably haven't heard of Frank Brilando. He raced in the 1948 and 1952 Olympics, but his long tenure as a Schwinn engineer earned him his place in cycling history. He, along with Al Fritz, created the Sting-Ray, Varsity and Continental bicycles during the 1960s.

You may think the Sting-Ray is an abomination only a 12-year-old boy could love, and you may turn up your nose at the Varsity and Continental. Before Brilando and Fritz developed them, however, few Americans had ridden a bicycle with a derailleur. Those Schwinns helped to popularize the multi-gear mechanisms and, arguably, paved the way for the Bike Boom of the '70s. If nothing else, the Varsity and Continental probably got American adults to ride bikes for the first time in decades.

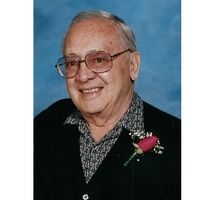

|

| Frank Brilando |

Brilando and Fritz also worked on the Airdyne full-body fan-resistance exercise bike. Once, in a conference room in Taiwan, Schwinn's brain trust were trying to figure out the proper crossover pattern (the relationship between the rider's arm position on the handles and foot position on the pedals) when Brilando realized the best pattern would be reflected in the arm and leg coordination of a baby crawling on the floor. "So Frank gets down on the floor and starts crawling like a baby," Fritz, who died in 2013, recalled.

Over the same weekend, Roland Della Santa, died at his Reno home, aged 72. He began building bicycle frames in 1970. One of his creations won the "best road frame" award at the 2009 North American Handbuilt Bicycle Show. Like Brilando, Della Santa also raced, and sometimes the frames people ordered were delayed because he was training so much.

|

| Roland Della Santa with his award-winning frame at the 2009 NAHBS. |

But a few frames of his in particular changed the course (pun intended) of American cycling. He took a certain 16-year-old into his home and admonished the young man for wearing a yellow jersey to his first race. "I didn't know you're only supposed to do that if you win the Tour de France," that rider recalls. Della Santa taught the young man about racing, and the European scene in particular. In fact, he inspired the youthful rider to plan a career in Europe.

Della Santa, of course, built frames for that young rider and became his first sponsor. When that rider achieved fame and fortune, Della Santa built the first stock steel frames sold under that cyclist's name.

Here's a hint to that rider's identity: He is the only rider from his country whose Tour de France victories haven't been vacated due to doping.

Yes, I am talking about Greg LeMond. You might say that Della Santa helped him to become what he became.