In earlier posts, I touched upon Schwinn’s history from its founding to its rise as America’s premier bike brand (or, as Sheldon Brown claimed, the only one with even a pretense of quality) and its descent, through all manner of mismanagement, into just another label you see in Walmart’s bike section.

Now, I have no reason to animus against Schwinn: I have owned and ridden bikes they made or branded and liked them for various reasons. In particular, I thought my early-‘90’s Criss-Cross was well-suited to its intended purposes and a good value.

Ironically, I acquired that bike not long before Schwinn filed for bankruptcy for the first time. People familiar with the industry have posited all sorts of reasons for it, but seem to agree that those reasons included

—dismissing mountain bikes and BMX—two genres Schwinn could easily have dominated—as passing fads

—relying on their antiquated Chicago factory, which couldn’t keep up with the increases and changes in demand wrought by The ‘70’s Bike Boom

—supplementing production by importing bikes from Japan (good), Taiwan (improved over time) and Hungary (did not improve, pretty bad to begin with)

—moving domestic production to Mississippi in order to avoid unions: a move that backfired because it was inaccessible to suppliers and shippers. Moreover, some say that while those bikes were lighter and more modern in design, the workmanship wasn’t anywhere near as good as what Chicago produced.

I think that all of those missteps Schwinn made over roughly a quarter-century can be traced to hidebound managerial thinking that too often results from nepotism, whether by blood or bonds of friendship.

In other words, it fell into the trap too many family-owned companies fall into: Keeping the business in the family becomes more important than considering new perspectives. An outsider could have told them, in the mid-1980s, “Mountain bikes are here to stay” and that good lightweight bikes could be TIG-welded (even if it isn’t as attractive as nice lugwork or filet brazing). Also, someone could have told them that they weren’t going to sell bikes to college students and other twenty-somethings with advertising and catalogs that seemed to say, “Buy Schwinn: the bike your grandparents rode.”

When Schwinn was finally freed from familial control—i.e., when it was sold during bankruptcy—it started to make necessary changes. But it may have been too late. Then it became indistinguishable from too many other bike brands.

So what got me to thinking about all of that? An open letter that the founders of Kona bicycles wrote to the bike industry. They are friends who met, long ago, while working in a bike shop. Three years ago, they sold Kona, which they founded in 1988 because they weren’t so young anymore and, I guess, all of the issues that arose from the COVID-19 pandemic wore them down. Now they’ve bought the company back because, they felt, the new owners—Kent Outdoors—were turning into something they didn’t recognize or like.

|

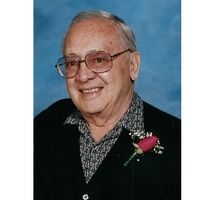

| Jake Heilbron and Don Gerhard, founders of Kona Bicycles |

What I found interesting about the letter is not only the origin story, if you will, but also a seeming recognition that, for all of their success, they—or, more precisely, Kona—could just as easily stepped into the same mental quicksand that sucked Schwinn away. More important, they understood what generated loyalty among a couple of generations of mountain (and other) bikers and that Kent wasn’t delivering it—just as a third generation of family ownership and the investment groups that bought the Schwinn name ignored what made it so esteemed for so long—and what would keep that esteem.