Last year, I wrote about the Campagnolo Gran Sport gruppo that was made from 1975 until 1985. It was Campy's "second line", behind the Record. Gran Sport parts echoed, for the most part, Record's designs, but omitted a few convenience features (such as infinitely-variable quick-release levers on the brake calipers) and weren't as nicely finished. That Gran Sport gruppo (not to be confused with the GS ensemble of the 1950s and early 1960s) was never terribly popular, at least here in the US, because top-of-the line Sun Tour Superbe and Shimano Dura-Ace components, which were prettier and lighter (and with derailleurs that shifted better) cost about the same as, or less than Gran Sport stuff. Also, as Brooks ("Retrogrouch") pointed out, Record components and gruppos could be had, via mail-order catalogues, for about the same amount of money as one would pay for Gran Sport in a shop.

Today, I am going to write about another "lost" gruppo. This one began production a few years after Gran Sport ended. And, unlike GS and Record, the components I'm about to mention were not intended for road racing. Rather, they were designed for the then-relatively-new sport of mountain biking.

In 1981, just before mountain biking spread from its original enclaves in northern California and New England, Shimano made its first touring ensemble. Now--again, I refer to "Retrogrouch"--it wasn't anywhere near as encompassing as Campagnolo's racing gruppos: It didn't include, for example, brakes or a seatpost. But it may have been the first attempt, however imperfect, at offering a coordinated set of drivetrain components for bicycle touring.

That ensemble, though, didn't lead to a Shimano domination of the touring market. Japanese manufacturers (and Trek) had been making good loaded touring bikes for several years, usually with a mixture of components like Sun Tour derailleurs with Sugino or Sakae Ringyo (SR) cranks, Dia Compe brakes and Sanshin hubs. Some of those bike manufacturers started to use the new Deore derailleurs, but in companion with the other components I've mentioned.

So, if dominating the touring market was Shimano's intention, they didn't succeed. However, mountain biking was about to take off, and that is where Deore components would find their niche. The year after they were introduced, they were tweaked and hubs, brakes and new brake and shift levers were added. So was the Deore XT, the first mountain bike group, born.

For the next four years, the Deore XT was Shimano's only mountain bike ensemble. In 1986, other, lower-priced groups and parts were introduced--including the Mountain LX in 1988. (Shimano had been making a road LX group.) Then, in 1990, a new set of components that had most of the features of the XT--and an attractive look--first saw the light of day.

If the Deore XT was the Dura Ace or Campagnolo Record of the mountain bike world, then the Deore DX was its Ultegra/600. It didn't take long for DX to appear on high-end mountain bikes from the likes of Trek, Gary Fisher and Klein, among other makers. Like the Campy Gran Sport Gruppo, it offered performance that differed imperceptibly, if at all, from the top-of-the line parts--at considerably lower cost.

If anything, the DX might have been even closer to XT than Gran Sport was to Record. For one thing, none of the essential or convenience features were sacrificed. The DX finishing work might not have been, on close inspection, quite up to XT standards, but almost nobody thought DX stuff was ugly. The chief difference, it seemed, was in weight, which had to do with materials. For example, the same parallelogram and knuckles were found on XT and DX derailleurs, but the DX had a steel pulley cage, in contrast to the alloy one on the XT.

Touring bikes were out of favor by the time DX came along in 1990, but the dedicated tourers that were being made (or re-vamped) by that time were often adorned with DX equipment. So were tandems and cyclo-cross bikes. (The latter is one reason why Shimano made a short-cage version of the DX rear derailleur.) Those who used DX equipment almost invariably praised it and, in fact, a fair number of riders are still riding with DX stuff they bought twenty-five years ago.

So why don't we see more of it today? Well, Shimano stopped production of Deore DX components in 1993. By that time, Shimano had upgraded the Deore LX lineup to the point that it was just about as good as DX, for about a third less money. At that time, both road and mountain bikes were moving from seven- to eight-speed cassettes. Shimano started to offer the LX with 8 speeds that year, but didn't "upgrade" the DX. So, people who bought new bikes or components were buying 8 speed--which, of course, meant Deore LX.

Also, that same year, Shimano introduced its new "super" mountain group: the XTR. With that addition, Shimano had ten different levels of mountain bike components (XTR, XT, DX, LX, Exage ES and LT and Altus A10, A20, C10 and C20). I guess the company decided that for 1994, it simply didn't want to make that many lines of parts. So, out went DX and the Exage and Altus lines. In their place came two levels of STX and two levels of Alivio at the bottom of Shimano's mountain bike lineup. The 8-speed Deore LX had, by 1995, firmly established itself as Shimano's "third" mountain bike line, roughly analogous to the 105 road group.

So...while Shimano produced Deore DX components for only three years, and production stopped more than two decades ago, many are still being ridden. (I ride a short-cage DX rear derailleur on Helene, my later-model Mercian mixte, with a 9-speed cassette.) That, I think, is a testament to how well they were made. Also, some of us simply prefer the look of them to what's made today.

Still, aside from those of us who know and ride them, almost nobody mentions Deore DX components anymore. Will they become Shimano's "forgotten" mountain bike group?

Today, I am going to write about another "lost" gruppo. This one began production a few years after Gran Sport ended. And, unlike GS and Record, the components I'm about to mention were not intended for road racing. Rather, they were designed for the then-relatively-new sport of mountain biking.

|

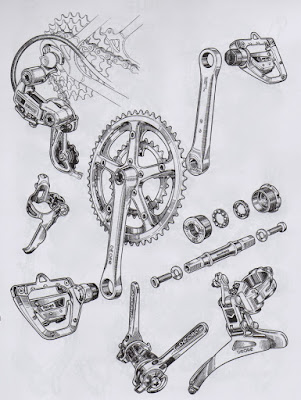

| Daniel Rebour drawing of the original Deore touring ensemble, 1981 |

In 1981, just before mountain biking spread from its original enclaves in northern California and New England, Shimano made its first touring ensemble. Now--again, I refer to "Retrogrouch"--it wasn't anywhere near as encompassing as Campagnolo's racing gruppos: It didn't include, for example, brakes or a seatpost. But it may have been the first attempt, however imperfect, at offering a coordinated set of drivetrain components for bicycle touring.

That ensemble, though, didn't lead to a Shimano domination of the touring market. Japanese manufacturers (and Trek) had been making good loaded touring bikes for several years, usually with a mixture of components like Sun Tour derailleurs with Sugino or Sakae Ringyo (SR) cranks, Dia Compe brakes and Sanshin hubs. Some of those bike manufacturers started to use the new Deore derailleurs, but in companion with the other components I've mentioned.

|

| 1982 Shimano Deore XT ensemble. |

So, if dominating the touring market was Shimano's intention, they didn't succeed. However, mountain biking was about to take off, and that is where Deore components would find their niche. The year after they were introduced, they were tweaked and hubs, brakes and new brake and shift levers were added. So was the Deore XT, the first mountain bike group, born.

For the next four years, the Deore XT was Shimano's only mountain bike ensemble. In 1986, other, lower-priced groups and parts were introduced--including the Mountain LX in 1988. (Shimano had been making a road LX group.) Then, in 1990, a new set of components that had most of the features of the XT--and an attractive look--first saw the light of day.

If the Deore XT was the Dura Ace or Campagnolo Record of the mountain bike world, then the Deore DX was its Ultegra/600. It didn't take long for DX to appear on high-end mountain bikes from the likes of Trek, Gary Fisher and Klein, among other makers. Like the Campy Gran Sport Gruppo, it offered performance that differed imperceptibly, if at all, from the top-of-the line parts--at considerably lower cost.

|

| Deore DX group, from the 1991 Shimano catalogue |

If anything, the DX might have been even closer to XT than Gran Sport was to Record. For one thing, none of the essential or convenience features were sacrificed. The DX finishing work might not have been, on close inspection, quite up to XT standards, but almost nobody thought DX stuff was ugly. The chief difference, it seemed, was in weight, which had to do with materials. For example, the same parallelogram and knuckles were found on XT and DX derailleurs, but the DX had a steel pulley cage, in contrast to the alloy one on the XT.

Touring bikes were out of favor by the time DX came along in 1990, but the dedicated tourers that were being made (or re-vamped) by that time were often adorned with DX equipment. So were tandems and cyclo-cross bikes. (The latter is one reason why Shimano made a short-cage version of the DX rear derailleur.) Those who used DX equipment almost invariably praised it and, in fact, a fair number of riders are still riding with DX stuff they bought twenty-five years ago.

So why don't we see more of it today? Well, Shimano stopped production of Deore DX components in 1993. By that time, Shimano had upgraded the Deore LX lineup to the point that it was just about as good as DX, for about a third less money. At that time, both road and mountain bikes were moving from seven- to eight-speed cassettes. Shimano started to offer the LX with 8 speeds that year, but didn't "upgrade" the DX. So, people who bought new bikes or components were buying 8 speed--which, of course, meant Deore LX.

Also, that same year, Shimano introduced its new "super" mountain group: the XTR. With that addition, Shimano had ten different levels of mountain bike components (XTR, XT, DX, LX, Exage ES and LT and Altus A10, A20, C10 and C20). I guess the company decided that for 1994, it simply didn't want to make that many lines of parts. So, out went DX and the Exage and Altus lines. In their place came two levels of STX and two levels of Alivio at the bottom of Shimano's mountain bike lineup. The 8-speed Deore LX had, by 1995, firmly established itself as Shimano's "third" mountain bike line, roughly analogous to the 105 road group.

So...while Shimano produced Deore DX components for only three years, and production stopped more than two decades ago, many are still being ridden. (I ride a short-cage DX rear derailleur on Helene, my later-model Mercian mixte, with a 9-speed cassette.) That, I think, is a testament to how well they were made. Also, some of us simply prefer the look of them to what's made today.

Still, aside from those of us who know and ride them, almost nobody mentions Deore DX components anymore. Will they become Shimano's "forgotten" mountain bike group?