"Brooks" of Retrogrouch frame is so kind. Last month, we wrote posts on the same topic, days apart, without prior consultation. He said, "You know what they say about great minds." Now, I would never, ever give myself such credit. Really!

Anyway, I wrote about a pair of Simplex bar end shifters, still in their original packaging, I saw at Tony's Bicycles in Astoria. I also espied a pair of Shimano bar-ends from the same era (1970s) in Tony's showcase.

Little more than a week later, Brooks wrote his excellent post about bar-end shifters in general. As he points out, they offer most of the advantages of integrated brake/shift levers ("brifters") without their vulnerability to damage--and expense. Brooks then discussed some of the different bar-end shifters made during the 1970s--when they seem to have been the most popular--and today.

He does mention something very interesting but almost entirely forgotten: Campagnolo has offered bar-end shifters at least since the early 1950s-- around the time they introduced the Gran Sport, their first parallelogram rear derailleur. The funny thing is that when that derailleur first saw the light of day, Campagnolo wasn't offering a down-tube shifter--which are commonly associated with classic Campy-equipped racing bikes-- to go with it. Why?

Well, it has to do with front derailleurs of the time. You see, front changers at the time weren't operated by Bowden-type cable controls. Instead, a direct lever moved the cage that shifted the chain from one chainring to another. These are sometimes jokingly referred to as "suicide shifters" because, in order to make the shift, riders had to spread their legs.

That arrangement also meant that riders did all of their shifting with their right hands. (Nearly all rear derailleurs are operated by levers on the right side of the bike.) During the 1949 Tour de France, dozens of riders switched their "suicide" levers to the then-new bar end (pass-vitesses) shifters developed by Jacques Souhart--but only for the front derailleur. They continued to use downtube shifters--mounted on the right side of the handlebars-- for their rear derailleurs.

That allowed the racers to continue to do all of their shifting with their right hands and would not have to switch their routine in the middle of a race. More important, perhaps, this new arrangement allowed riders to make front shifts without interrupting their pedal strokes: a very important feature when beginning a sprint or a downhill.

It just happened that Monsieur Souhart was Campagnolo's Paris distributor and thus had Signore Tullio's ear. Apparently, Souhart as well as a number of racers convinced him of the bar-end shifter's superiority. That may be the reason why the first Campagnolo Gran Sport gruppo included bar-end, but not downtube, shifters.

Interestingly, a few years later, Souhart created a front derailleur that more closely resembles modern mechanisms, in that the cage moved upward as it moved outward. (Older mechanisms, like the "suicide" derailleurs, moved straight across.) He also made a "detented" (indexed) system of his bar-end lever to actuate the front derailleur. Campagnolo would not adopt that new feature of his bar-end shifter, but it did incorporate his front-derailleur innovation into their lineup.

Bar-end shifters' popularity among road racers was short-lived, mainly because downtube shifters, with their shorter cables, were lighter and offered snappier, more precise shifting, especially with the kinds of derailleurs available in the 1950s. But the fact that bar-ends allow cyclists to shift without removing their hands from the handlebars made them popular with cyclo-cross racers, who ride on rough terrain. They also became the preferred shifters of some touring cyclists, especially after SunTour introduced its ratcheted "BarCon" and Shimano its spring-loaded levers during the 1970s. In fact, some bikes designed for fully-loaded touring, such as Trek's original 720 (not to be confused with the later 720) came with BarCons as standard equipment, whether or not they were adorned with SunTour derailleurs.

Anyway, I wrote about a pair of Simplex bar end shifters, still in their original packaging, I saw at Tony's Bicycles in Astoria. I also espied a pair of Shimano bar-ends from the same era (1970s) in Tony's showcase.

Little more than a week later, Brooks wrote his excellent post about bar-end shifters in general. As he points out, they offer most of the advantages of integrated brake/shift levers ("brifters") without their vulnerability to damage--and expense. Brooks then discussed some of the different bar-end shifters made during the 1970s--when they seem to have been the most popular--and today.

He does mention something very interesting but almost entirely forgotten: Campagnolo has offered bar-end shifters at least since the early 1950s-- around the time they introduced the Gran Sport, their first parallelogram rear derailleur. The funny thing is that when that derailleur first saw the light of day, Campagnolo wasn't offering a down-tube shifter--which are commonly associated with classic Campy-equipped racing bikes-- to go with it. Why?

Well, it has to do with front derailleurs of the time. You see, front changers at the time weren't operated by Bowden-type cable controls. Instead, a direct lever moved the cage that shifted the chain from one chainring to another. These are sometimes jokingly referred to as "suicide shifters" because, in order to make the shift, riders had to spread their legs.

That arrangement also meant that riders did all of their shifting with their right hands. (Nearly all rear derailleurs are operated by levers on the right side of the bike.) During the 1949 Tour de France, dozens of riders switched their "suicide" levers to the then-new bar end (pass-vitesses) shifters developed by Jacques Souhart--but only for the front derailleur. They continued to use downtube shifters--mounted on the right side of the handlebars-- for their rear derailleurs.

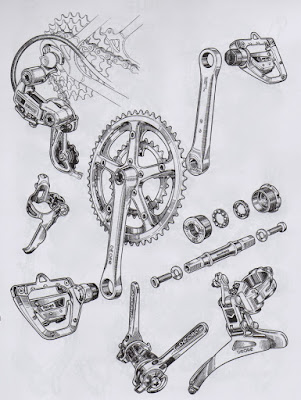

|

| From "Stronglight" in Flickr |

That allowed the racers to continue to do all of their shifting with their right hands and would not have to switch their routine in the middle of a race. More important, perhaps, this new arrangement allowed riders to make front shifts without interrupting their pedal strokes: a very important feature when beginning a sprint or a downhill.

|

| "Suicide" front derailleur. From Dave Moulton's blog. |

It just happened that Monsieur Souhart was Campagnolo's Paris distributor and thus had Signore Tullio's ear. Apparently, Souhart as well as a number of racers convinced him of the bar-end shifter's superiority. That may be the reason why the first Campagnolo Gran Sport gruppo included bar-end, but not downtube, shifters.

Interestingly, a few years later, Souhart created a front derailleur that more closely resembles modern mechanisms, in that the cage moved upward as it moved outward. (Older mechanisms, like the "suicide" derailleurs, moved straight across.) He also made a "detented" (indexed) system of his bar-end lever to actuate the front derailleur. Campagnolo would not adopt that new feature of his bar-end shifter, but it did incorporate his front-derailleur innovation into their lineup.

Bar-end shifters' popularity among road racers was short-lived, mainly because downtube shifters, with their shorter cables, were lighter and offered snappier, more precise shifting, especially with the kinds of derailleurs available in the 1950s. But the fact that bar-ends allow cyclists to shift without removing their hands from the handlebars made them popular with cyclo-cross racers, who ride on rough terrain. They also became the preferred shifters of some touring cyclists, especially after SunTour introduced its ratcheted "BarCon" and Shimano its spring-loaded levers during the 1970s. In fact, some bikes designed for fully-loaded touring, such as Trek's original 720 (not to be confused with the later 720) came with BarCons as standard equipment, whether or not they were adorned with SunTour derailleurs.