Today is Bastille Day.

So, why have I posted a photo of a tide rolling in?

No, I am not making a hackneyed metaphor for the mobs that stormed the prison that became a symbol of monarchial tyranny and class stratification. Nor am I making an equally tired cliche about the cycles of history.

I took that photo on Bastille Day, almost. Actually, it's from a couple of days after, just ahead of a Tour de France stage--in the French Alps.

That scene is of something to which I've alluded in other posts. I took the photo as I pedaled above clouds. To this day, I can't say whether I felt more elation over rising above the clouds or reaching the top of the mountain, which I did a bit later.

Now I am going to reveal one of my dim, dark secrets:

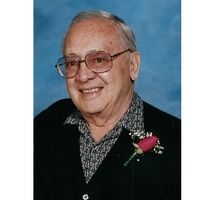

Yes, that's what I looked like on 17 July 2001, a bit more than a year before I started my gender affirmation process. (I am squinting because, at high altitudes, the sun is more intense.) Not only was my world different; so was the world. For one thing, I asked some random stranger to take that photo: In the days before i-phones, it was more difficult to take "selfies" without special equipment. Also, 2001 was the last year of the franc and lira: On my next trip to France, three years later, I'd be paying in euros. And less than two months after I rode to the top of l'Alpe d'Huez, ahead of the Tour peloton, the terrible events of 11 September would change so much else.

A couple of days after that climb, I would ascend to another iconic Tour climb: the col du Galibier. I described that climb, and how it--or, more precisely, descending from it and crossing the valley--led me to, among other things, becoming the midlife cyclist who authors this blog. (See this and this.)

So, on this Bastille Day--as the Tour de France climbs and descends through its second day in the Alps--I am writing in part to celebrate the country which I feel almost as much kinship as my own and ascending some of its most difficult climbs. But I now realize that I am paying homage to the person--known as Nicholas, Nick or Nicky-- who brought me to the part of the journey I've recounted in this blog. I hope I am honoring him in the way he deserves.

Oh, and today is the anniversary of the day I gave up his name and assumed mine, two years after I ascended those mountains. I remember feeling, on that day--Bastille Day--that I felt more free, that I had climbed another mountain.

Whether they finish first, last or somewhere in between, the riders in today's Tour stage will always have that. Just ask Phillipa York, nee Robert Millar.

Note: I apologize for the poor quality of the images. I'm still learning how to use my iPhone to take pictures of old pictures!