The star was ascending. Or so it seemed.

The time: late 1970's-early 1980s. The place: North America.

The '70's Bike Boom was over. Some people discovered bicycle touring during the heady summer of Bikecentennial. Not many stuck with it: careers and families and such detoured them. (Also, some had a "been there, done that" attitude after touring the country.) And whatever awareness people might have developed about bike touring, or any type of cycling done by adults, didn't translate into a lifestyle of which cycling would be an integral part. They continued to drive to work, school and for shopping and recreational activities. They might take the bike for a spin in the park, but it was a novelty, much as taking a horseback ride during a vacation is for many people.

Still, there were some signs that the United States and Canada might one day join some of European countries and Japan among the elite cycling nations. Nancy Burghart had dominated women's racing during the 1960's. During the following decade, a new generation of American women would dominate the field to an even greater degree. In fact, one could argue that Mary Jane ("Miji") Reoch, Sue Novara, Connie Carpenter and Rebecca Twigg turned the US into the first "superpower" of women's cycling.

Men's racing on this side of the Atlantic (and Pacific) was also improving by leaps and bounds, though they were pedaling through longer shadows cast by such riders as Anquetil, Mercx and Hinault. Still, during the period in question, the world began to notice American male cyclists, especially after they took home seven medals, including three golds, in the 1984 Olympics: the first time American men won any hardware since the 1912 games. (Connie Carpenter and Rebecca Twigg won the gold and silver, respectively, in the inaugural women's Olympic road race that year.)

Canada wasn't about to be left out of the picture. In those same Olympic games, Steve Bauer took the silver medal in the men's road race, and Curt Harnett did the same in the 1 km time trial. In the road race, someone you've probably heard of finished 33rd: Louis Garneau. Yes, the one with the line of bike clothing and helmets.

Although Bauer's and Harnett's victories were sweet for our friends to the north, they highlighted the absence of another rider who, many believed, could have won, or at least challenged for, a medal: Jocelyn Lovell.

Six years earlier, he'd won three gold medals at the Commonwealth Games. Later that same year, captured the silver medal at the World Cycling championships. Those victories highlighted a career that saw him win medals in other Commonwealth as well as Pan American games, as well as numerous national titles, throughout the 1970s. He also represented Canada in the 1968, 1972 and 1976 Olympics--the latter of which were held in Montreal.

Like the United States, Canada boycotted the 1980 Summer Olympics, in protest of the then-Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan. Thus Lovell didn't make the trip to Moscow, where the Games were held. He turned 30 during the course of the games. It seemed, then, that if Lovell were to ride in the 1984 Olympics, they would probably be his last.

But he never had that opportunity. A year before the opening ceremony in Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, tragedy befell Jocelyn Lovell. Late in the afternoon of 4 August 1983, he was out on one of his daily training rides near his Missisauga, Ontario home. A pair of dump trucks approached him from behind as he crested a hill. The first swung around him. The second ploughed over him.

That he wasn't killed was a miracle. However, from that moment onward, he would never move any part of his body below his shoulders, ever again.

According to friends and acquaintances, he never accepted his fate. He always said that one day, he'd be on a bike again. He may well have said that on Friday, 3 June: the day his battle ended, at age 65.

Such an ending is particularly sad for someone who was noted for his souplesse: his fluid form astride a bicycle. Observers remarked that he and his bike simply seemed to belong together. The terrible irony is that someone who had such physical grace would have to spend half of his life completely unable to use it. He did, however, become an advocate for spinal cord research and other related causes.

Although relatively few in the US know about him, any of us who are cyclists and benefit in any way from the current interest in cycling owe him a debt of gratitude: He helped to put our continent on the cycling map. And he always kept his hope alive. What is more American than that?

The time: late 1970's-early 1980s. The place: North America.

The '70's Bike Boom was over. Some people discovered bicycle touring during the heady summer of Bikecentennial. Not many stuck with it: careers and families and such detoured them. (Also, some had a "been there, done that" attitude after touring the country.) And whatever awareness people might have developed about bike touring, or any type of cycling done by adults, didn't translate into a lifestyle of which cycling would be an integral part. They continued to drive to work, school and for shopping and recreational activities. They might take the bike for a spin in the park, but it was a novelty, much as taking a horseback ride during a vacation is for many people.

Still, there were some signs that the United States and Canada might one day join some of European countries and Japan among the elite cycling nations. Nancy Burghart had dominated women's racing during the 1960's. During the following decade, a new generation of American women would dominate the field to an even greater degree. In fact, one could argue that Mary Jane ("Miji") Reoch, Sue Novara, Connie Carpenter and Rebecca Twigg turned the US into the first "superpower" of women's cycling.

Men's racing on this side of the Atlantic (and Pacific) was also improving by leaps and bounds, though they were pedaling through longer shadows cast by such riders as Anquetil, Mercx and Hinault. Still, during the period in question, the world began to notice American male cyclists, especially after they took home seven medals, including three golds, in the 1984 Olympics: the first time American men won any hardware since the 1912 games. (Connie Carpenter and Rebecca Twigg won the gold and silver, respectively, in the inaugural women's Olympic road race that year.)

Canada wasn't about to be left out of the picture. In those same Olympic games, Steve Bauer took the silver medal in the men's road race, and Curt Harnett did the same in the 1 km time trial. In the road race, someone you've probably heard of finished 33rd: Louis Garneau. Yes, the one with the line of bike clothing and helmets.

Although Bauer's and Harnett's victories were sweet for our friends to the north, they highlighted the absence of another rider who, many believed, could have won, or at least challenged for, a medal: Jocelyn Lovell.

Six years earlier, he'd won three gold medals at the Commonwealth Games. Later that same year, captured the silver medal at the World Cycling championships. Those victories highlighted a career that saw him win medals in other Commonwealth as well as Pan American games, as well as numerous national titles, throughout the 1970s. He also represented Canada in the 1968, 1972 and 1976 Olympics--the latter of which were held in Montreal.

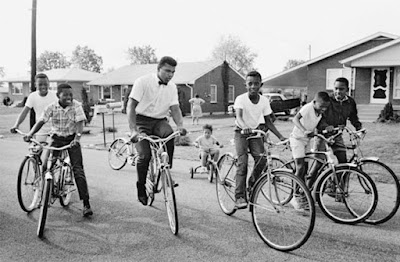

|

| Lovell at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal |

Like the United States, Canada boycotted the 1980 Summer Olympics, in protest of the then-Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan. Thus Lovell didn't make the trip to Moscow, where the Games were held. He turned 30 during the course of the games. It seemed, then, that if Lovell were to ride in the 1984 Olympics, they would probably be his last.

But he never had that opportunity. A year before the opening ceremony in Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, tragedy befell Jocelyn Lovell. Late in the afternoon of 4 August 1983, he was out on one of his daily training rides near his Missisauga, Ontario home. A pair of dump trucks approached him from behind as he crested a hill. The first swung around him. The second ploughed over him.

That he wasn't killed was a miracle. However, from that moment onward, he would never move any part of his body below his shoulders, ever again.

According to friends and acquaintances, he never accepted his fate. He always said that one day, he'd be on a bike again. He may well have said that on Friday, 3 June: the day his battle ended, at age 65.

Such an ending is particularly sad for someone who was noted for his souplesse: his fluid form astride a bicycle. Observers remarked that he and his bike simply seemed to belong together. The terrible irony is that someone who had such physical grace would have to spend half of his life completely unable to use it. He did, however, become an advocate for spinal cord research and other related causes.

Although relatively few in the US know about him, any of us who are cyclists and benefit in any way from the current interest in cycling owe him a debt of gratitude: He helped to put our continent on the cycling map. And he always kept his hope alive. What is more American than that?